Warren Buffett is sitting on more cash than at any point in his career. If you own U.S. stocks that depend on healthy consumer spending, that should at least make you pause.

While the trades near all-time highs and unemployment sits below 4%, student loan defaults among prime-credit borrowers have exploded 1,753% year-over-year, credit delinquencies in affluent ZIP codes have surged 80%, and a cascade of white-collar layoffs is about to accelerate the damage.

For investors still betting on continued consumer spending, the data suggests Buffett is reading a different script entirely.

The 1,753% Alarm Buried In Student Loans

One of the clearest early signals is coming from student debt.

In Q3 2025, the share of borrowers moving into serious delinquency jumped to 14.26%. In the same quarter a year earlier, that rate was just 0.77%. On a percentage basis that is a rise of about 1,753% in twelve months.

Even more worrying is who is defaulting. Roughly a quarter of the borrowers falling behind now have prime or better credit scores. In past cycles, prime borrowers made up less than 5% of student loan defaults. These are not fringe borrowers. These are the people who were supposed to be the safest part of the market.

Picture a football team that suddenly loses its quarterback, running back, and tight end in the same quarter. The scoreboard might not move right away, but anyone watching knows the second half will look different. That is roughly what is happening to America’s professional class. The group that was supposed to support decades of consumption growth is taking hits all at once.

The stress is not limited to student loans. Between Q3 2022 and Q1 2025, credit card delinquencies in the the highest income zip codes climbed about 80%. Ninety day delinquency rates there moved from 4.1% to 7.3%. These are neighborhoods where people drive late model German cars and book ski weeks in places like Aspen. When that group starts paying cards late, the problem is no longer about the bottom of the income distribution.

A Spending Slowdown That Employment Data Hides

Consumer spending still accounts for roughly 70% of U.S. GDP. In Q2 2025, that engine barely grew at all. Spending was flat to slightly up, even as financial news shows spent the summer cheering strong job numbers.

The basic issue is that headline employment data counts jobs, not purchasing power. A software engineer earning $120,000 who gets laid off and then takes two gig roles for a combined $45,000 shows up in the statistics as employed. On paper nothing looks broken. In real life, household spending capacity just dropped by $75,000 a year.

McKinsey’s Q3 2025 research points in the same direction. About 38% of white-collar job changes now involve a pay cut of at least 20%. Those moves still look like employment gains in the official reports, even though they reduce future spending.

You can see the strain in search behavior as well. Google Trends shows terms like “cash advance”, “sell my car”, “second job”, and “plasma donation” hitting multi year or all time highs in 2024 and 2025. When college educated professionals are hunting for plasma donation centers, the economy is not in a mild soft patch. Something in the income side of the story has gone wrong.

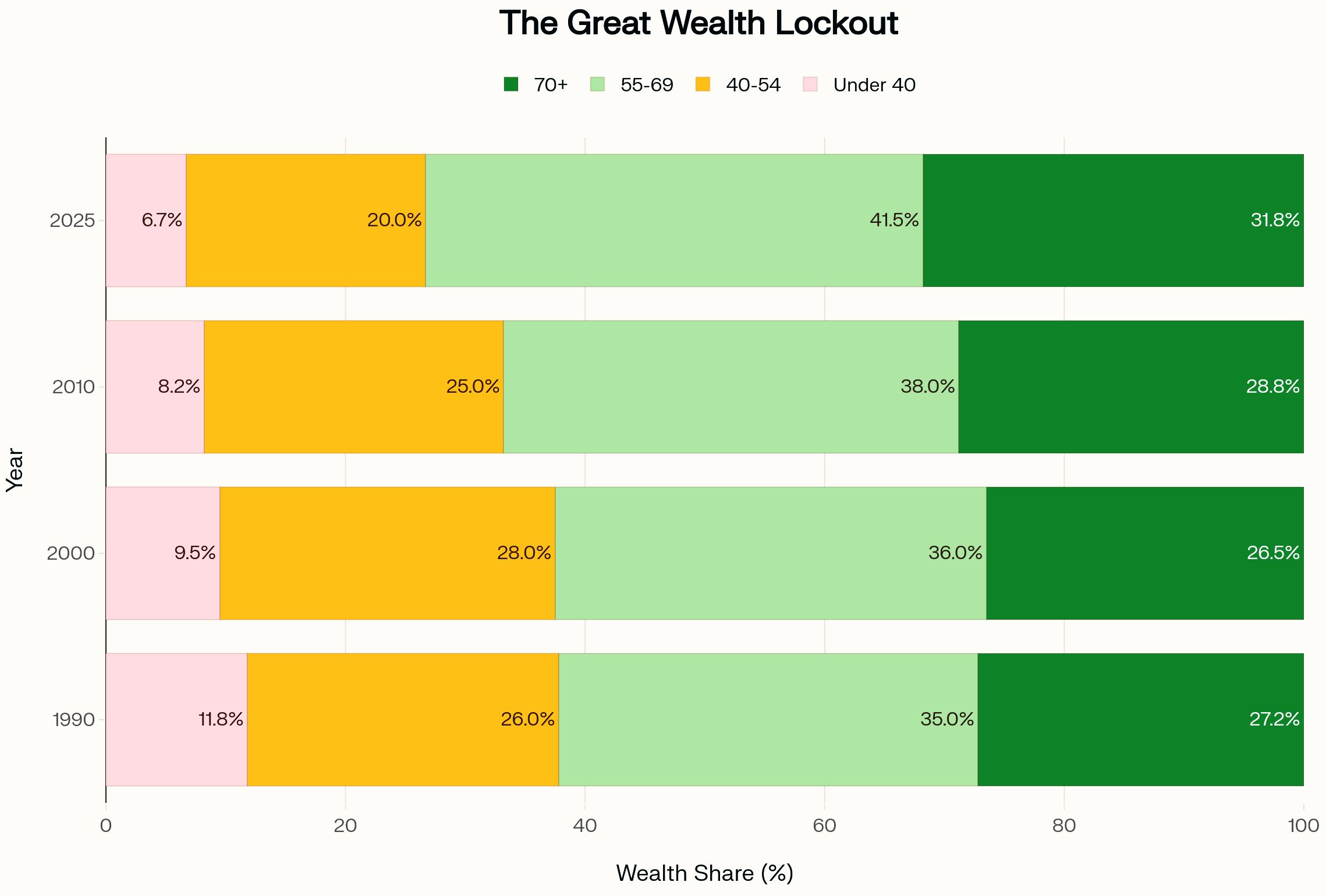

Generational wealth distribution has radically shifted, with Americans under 40 seeing their wealth share cut in half while those 55+ now control nearly three-quarters of all U.S. wealth

The Great Wealth Lockout

The other structural piece is the way wealth has shifted between generations.

In 1990, Americans under 40 held about 11.8% of total wealth. Today that share is roughly 6.7%. In other words, younger households now control about 43% less wealth than their counterparts did thirty five years ago.

At the same time, the share owned by older households has swollen. Americans over 70 have roughly doubled their slice of the pie. People over 55 now hold about 73% of all wealth. When a group that owns nearly three quarters of the assets accounts for less than a fifth of consumption, the usual growth math stops working.

Millennials and Gen Z together hold only about 10.7% of total wealth, despite making up a large share of the population. They are supposed to be in peak years for forming households, buying cars, and raising children. Instead, many are stuck renting, delaying families, and servicing old debt.

You can see that squeeze most clearly in housing.

The average first time homebuyer in the United States is now around 40 years old, a record. The income needed to afford the median priced home is roughly $141,000, about double the median salary. First time buyers make up only about 21% of purchases, down from more than 40% in 2009.

That backdrop helps explain why the Trump administration has floated 50 year mortgages and why Fannie Mae scrapped minimum credit score requirements in November. These moves are not bold innovations. They are attempts to conjure extra demand from buyers who simply do not earn enough to support current prices.

On paper, a 50 year loan trims the monthly payment by roughly $119 to $400 compared with a 30 year mortgage, depending on the size of the loan. The trade off is brutal. On a $450,000 purchase at a 6.25% rate, total interest over 50 years comes to about $1.02 million. The same loan over 30 years costs roughly $547,000 in interest. After ten years on the 50 year schedule, only about 4% of the principal is gone. After twenty years, just 11%.

When policymakers embrace terms that lopsided, it is a pretty strong tell that they know traditional buyers are missing. History offers a useful comparison. In the years before the 2008 crisis, lenders rolled out features like Option ARM loans with negative amortization, stated income mortgages, and adjustable rate products that reset sharply higher. Each step was sold as a way to “expand access” to homeownership. In reality, those designs admitted that the old income base could not carry the new prices.

The modern 50 year mortgage plays a similar role. It signals that the income needed to support home values has moved far away from what typical buyers actually earn.

What Bank Credit Officers Are Already Telling You

You do not need to wait for official layoff announcements in early 2026 to see the pressure building. The Federal Reserve’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey is already flashing an early warning.

In recent quarters, the survey has shown “moderate net tightening” in lending standards, especially in consumer credit. If that language shifts to “substantial tightening” during the next few reports, history says you are looking at a four to six month lead time before a more serious consumer credit crunch.

Regional banks give an even closer to real time view. When their quarterly calls start to feature phrases like “elevated delinquency rates” or “tighter underwriting” in consumer books, it is a cue to re examine positions. The October 2025 survey data already points to continued tightening across most consumer loan categories, which suggests the credit contraction phase is still early.

The Q1 2026 Pressure Point

If you are trying to figure out when this slow burn turns into something markets cannot shrug off, Q1 2026 is the obvious place to look.

Large employers are in the middle of major white-collar cuts. Amazon is reducing its office workforce by roughly 10%, or about 14,000 roles. UPS plans to drop around 14,000 management jobs. Target is trimming about 1,800 corporate positions. On top of that, Anthropic’s CEO has warned that AI could wipe out half of all entry level white-collar roles within one to five years, pushing unemployment into a 10 to 20% range in a severe case.

The rough sequence looks like this.

- Q4 2025 to Q1 2026: companies finish cost cutting, and newly unemployed professionals hit the job market.

- Q2 2026: many of those households run into student loan bills and credit card balances at the same time.

- Q3 to Q4 2026: credit quality deteriorates, banks respond by tightening standards further.

- 2027: housing demand falls sharply as would be buyers cannot qualify under any reasonable terms.

In past cycles, the delay between job loss and clear credit stress is usually two to three months. If firms like Amazon, UPS, and Target complete their layoffs by the middle of January, you would expect credit indicators to look much worse by March or April. That is a smaller window than many traders seem to be assuming.

What Buffett Is Really Reacting To

The usual way to frame Buffett’s caution is through valuations. The so called Buffett Indicator, which compares total U.S. market value to GDP, sits at about 217% right now. That level is more than 2.2 standard deviations above its long term average. In the past, Buffett has described readings above 200% as “playing with fire”.

That valuation gap matters, but it does not fully explain his behavior. The better image is a tall tower built on a narrow base.

Over the past decade, the country has been pulling blocks from the bottom of the tower. Younger generations gave up ground on wealth share, income growth, and access to homeownership. At the same time, more blocks kept getting stacked on top in the form of higher asset prices that mainly helped people who already owned plenty of assets.

From a distance the structure still looks stable. is positive. is low. Stock indices sit near highs. What Buffett sees, in my view, is that the missing blocks at the base are starting to matter. Once enough of them disappear, the tower does not wobble for long. It simply tips.

Employment data shows improving conditions while consumer financial stress indicators accelerate sharply, revealing a fundamental disconnect in economic health signals

How To Position Around This

For investors, the message is not that the world ends tomorrow. It is that the market still prices in a level of future consumption that the current income trends probably cannot support.

The most obvious place to watch is consumer discretionary. That group functions as the early warning gauge for household demand. It has already lagged the wider market. The sector ETF, , is down about 8% year to date, while consumer staples, represented by , are roughly flat.

Regional banks with heavy exposure to consumer credit are another stress point. Names like , , and trade at discounts to the largest banks despite carrying similar or higher historical risk premiums. If delinquencies keep climbing, that gap can widen.

Real estate investment trusts tied to retail and consumer spending also look vulnerable. The retail focused REIT segment is down around 12% this year yet still seems to assume steady demand. That is a fragile assumption if households are tapped out.

In that environment, it makes sense to tilt toward staples over discretionary, value over high growth, and a higher share of cash than usual for at least the next six to twelve months.

The timing element matters. These assets have not crashed. They are in the middle of repricing. Buffett does not usually rush to deploy cash after the damage is obvious. He tends to move when prices are adjusting but before panic headlines show up every day. The next ninety days will go a long way toward deciding which way this repricing breaks.

Reading The $382 Billion Signal

When the most successful long term investor in modern markets holds more cash than the annual output of many countries, sells stocks into a rising market, and refuses to buy back his own shares, you have to ask a simple question. Is he misreading the moment, or are the standard comfort metrics missing the point?

Look at the pieces together. Prime borrower defaults are exploding. High income credit card delinquencies are climbing. Big companies are still cutting white-collar staff. Banks are tightening lending standards. Wealth is locked up with older households who naturally spend less. None of that fits with a story of endless consumer strength.

I do not think Buffett is betting on a minor dip. He is waiting for a repricing that brings asset values back in line with the actual earning power of the people who are supposed to buy those assets. If that is right, the cash he is sitting on will look less like caution and more like preparation.